louisa townsend

Louisa Townsend was born in London on 24 September 1831 and baptised at St James, Westminster on 6 December. She was the daughter of Thomas Henry Townsend and Harriet Willis. Louisa and her eight siblings enjoyed a life of comfort and privilege in their large home on Charles Street in Westminster and years later, Louisa described their middle class upbringing — ‘We were taught what all properly brought up young girls were supposed to know in those days including music and French. We never had to do domestic work.’

The family obviously had an adventurous spirit as three of Louisa’s elder brothers emigrated in the 1850s; James Townsend travelled widely before settling briefly in Australia and finally India, Philip Henry also emigrated to Australia while George emigrated to America. Louisa and her sister may have been influenced by their brother’s adventures as well as the social trends of the day when they decided to emigrate to Vancouver Island.

Louisa and Charlotte were born at a time of rapid social and economic change. By the 1830s, the effects of the Industrial Revolution had altered the landscape of rural and urban life in England — the mechanization of agriculture and the creation of new factories in cities resulted in rapid urbanisation as workers left the countryside in search of employment in factories. But the urban centres could not cope with the massive influx and a lack of facilities and infrastructure resulted in problems of pollution, public health, disease, poverty and crime so well documented in Dickens’ novels. The Poor Law of 1834 only served to increase the pressure on the poor by forcing them into the workhouse before they could receive parish relief. As the pressure for action increased, many social organizations and politicians saw emigration as a viable solution to both the problem in England and in the colonies. They believed that assisted emigration would stabilize the social situation at home and give those remaining in England a better chance to succeed and it would also allow Britain to secure its imperialist hold on the colonies by populating them with English settlers.

In 1837, the British Parliament created an Agent General for Emigration to oversee efforts to encourage and assist emigration to the colonies. Their efforts were successful and by 1845, over 300 000 young men had emigrated to the colonies and the exodus continued for the next two decades. Many young men sought new lives and new opportunities abroad while others sought their fortunes in the gold fields of Australia and British Columbia. But the loss of so many young men was not without consequences as the Census of 1861 showed, in England and Wales alone there were 200 000 more women between the age of 20 and 25 than men. As Louisa and her sisters reached a marriageable age, there were few potential suitors available to them.

Victorian society offered few opportunities for educated, middle class women to obtain employment and gain independence. Even when entering ‘acceptable’ occupations as teachers or governesses, they faced stiff competition for placements. The limited educational opportunities for girls resulted in a limited demand for female teachers and the growing number of unmarried women meant there were more women seeking employment as governesses than there were available positions.

In the 1850s, a group of liberal feminists known as the Langham Place Group sought to increase the employment opportunities for women. They published the English Woman’s Journal in 1858 and used it as a vehicle to publicize their views on the role of women in society and their right to employment—‘every woman should be free to support herself by the use of whatever faculties God has given her without obstruction by prejudice or legislation.’ But change was slow to materialize and the group soon proposed emigration for educated women as an option to obtain full employment outside the home. In her address before London’s Social Sciences Congress in 1861, Maria S. Rye encouraged women to ‘teach your protégés to emigrate; send them where the men want wives, the mothers want governesses, where the shopkeepers, the schools, and the sick will thoroughly appreciate your exertions and heartily welcome your women.’

They began to work with existing emigration societies, including the Columbia Emigration Society, to raise funds to send young women to the colonies to work as domestic servants, nurses and governesses. They held lectures in London, wrote letters to the editor of the The Times and placed advertisements promoting their plans. At the same time, the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia were receiving a great deal of positive attention in the popular press as a destination offering both opportunity and an agreeable climate.

Louisa and her sister were most likely influenced by these newspaper reports when they set their minds on emigrating to Vancouver Island where they planned to teach music and French. Their family did not initially support their desire to emigrate but as Louisa later recounted ‘at last our relatives consented to let us come out to Canada’ and they booked their passage on the SS Tynemouth. The three masted, iron steamship had a passenger list that included young men headed for the Cariboo gold fields, families seeking a new life in the colony and a party of 57 young women travelling under the auspices of the Columbia Emigration Society.

Louisa and Charlotte travelled from London by train to the port of Dartmouth in Devon with their elder sister Elizabeth as escort. They transferred to the Tynemouth on tenders and set sail on 28 May 1862. Their family paid their passage and the sisters shared a second class cabin complete with visiting cards tacked above the door. They imagined they would find all the comforts of home in the new colony and packed accordingly — ‘We had beautiful clothes for our journey. Quantities of fine lingerie, dainty dresses and smart hats, boxes of handkerchiefs and lace mits. Then we brought our piano, and a beautiful sewing machine, a Wheeler and Wilson. No one on the ship had half the luggage we had.’ They even brought a chair that remains in the family to this day.

The voyage from Dartmouth lasted four months and took them to the Falkland Islands and around Cape Horn to San Francisco before finally arriving in Victoria Harbour on 17 September. With its cargo of eligible young woman, the Tynemouth was known as ‘the brideship’ and its arrival was eagerly anticipated by the many prospective grooms in Victoria. Harriet Townsend had arranged for her daughters to stay with a family friend, Mrs. Pringle, and her clergyman husband on the mainland but after such a long journey, Charlotte had no desire for another trip and stayed in Victoria. Louisa travelled to Fort Hope with Mrs. Pringle but her time there was not a happy one — ‘I used to cry myself to sleep every night. I slept in a garret room with big cracks that let in the rain. The houses were all very poorly built. I was supposed to be a sort of companion; but though they kept Chinese help, there were tasks to do which were distasteful to me, for I had been brought up with servants in the house at home and all sorts of comforts.’

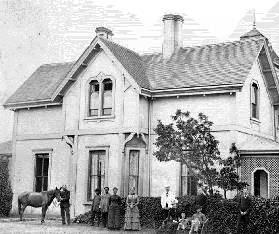

After three months in Fort Hope, Louisa returned to Victoria to act as a companion and governess for the Pidwell family at their home on Humboldt Street. The social scene in Victoria was more to Louisa’s taste as she was able to participate in past times she enjoyed in England including horseback riding, playing the piano, singing and dancing. After leaving the Pidwells, she took a position with the Rhodes family at Maplehurst on Blanshard Street. The Rhodes family entertained often and Louisa enjoyed attending their balls and parties.

Her sister Charlotte married Alfred Allat Townsend at St John’s Church on 26 March 1864 and Louisa lived with Charlotte and Alfred until she married two years later. In 1865, Louisa met Edward Mallandaine at St John’s Church where they both sang in the choir.